C.E. Blevins

“I really believe God wants me to make these bird egg replicas. I prayed and prayed about it fifteen years ago. I just couldn’t figure out how to make clay into the egg shape. It’s a hard shape to duplicate. And God talked to me in a dream one night. He showed me how to make the eggs and I’ve been making all I can since then. The reason I make them is because I have never seen anything more beautiful than a bird’s egg. And I just want people to be able to see them without bothering the birds."

This is the mission of “The Egg Man of Cohutta." A retired Southern Baptist minister, retired public school art resource teacher (who taught art to public school students via television), and retired missionary to Zambia, Africa, Blevins's goal now is to continue building the world’s largest collection of species-specific wild bird egg replicas.

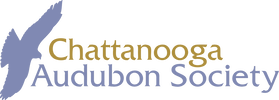

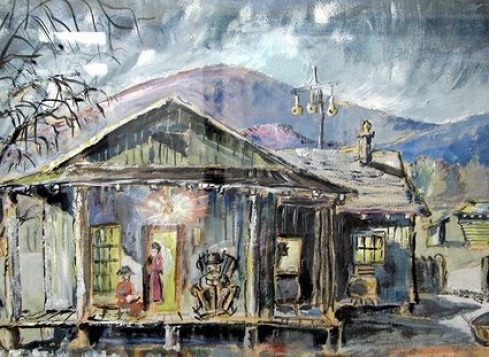

C. E. Blevins was born in Robbins, Tennessee in 1924.His father, Shade Blevins, was an itinerant schoolteacher, who sometimes had to travel to Detroit to find work with General Motors. With C. E.'s mother, Ella Shoemaker Blevins, Shade raised nine children.C. E. (Cleatis Edral) was the seventh child.Robbins is located in upper east Tennessee—Scott County.Visitors to the area today (near Rugby and Jamestown, Tennessee) will recognize the area as undeniably “Appalachian."Even now the main industry is lumber or coal, and in the early 1900's, bootlegging would have been another option.As you can see from C. E.’s painting of his birthplace home, his parents had to grow much of their food.

This is the mission of “The Egg Man of Cohutta." A retired Southern Baptist minister, retired public school art resource teacher (who taught art to public school students via television), and retired missionary to Zambia, Africa, Blevins's goal now is to continue building the world’s largest collection of species-specific wild bird egg replicas.

C. E. Blevins was born in Robbins, Tennessee in 1924.His father, Shade Blevins, was an itinerant schoolteacher, who sometimes had to travel to Detroit to find work with General Motors. With C. E.'s mother, Ella Shoemaker Blevins, Shade raised nine children.C. E. (Cleatis Edral) was the seventh child.Robbins is located in upper east Tennessee—Scott County.Visitors to the area today (near Rugby and Jamestown, Tennessee) will recognize the area as undeniably “Appalachian."Even now the main industry is lumber or coal, and in the early 1900's, bootlegging would have been another option.As you can see from C. E.’s painting of his birthplace home, his parents had to grow much of their food.

Most of the land around Robbins is rolling hill country, varyingly steep and difficult to cultivate.Only a short distance, as the crow flies, to the west of Robbins, the Cumberland Plateau provides some of Tennessee’s finest farmland.But to the residents of Robbins, the big three, economically speaking (timber, coal, and moonshine) were the common choices of settlers.It was for this reason Ella and Shade Blevins decided to move their family to a sharecropping farm in the Sequatchie Valley, in 1931.

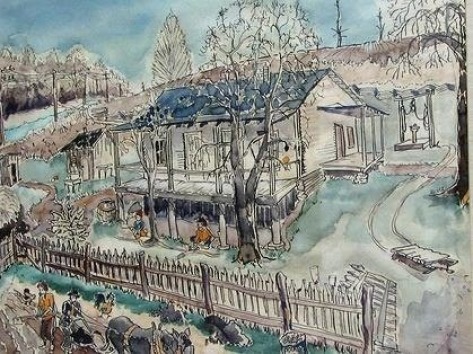

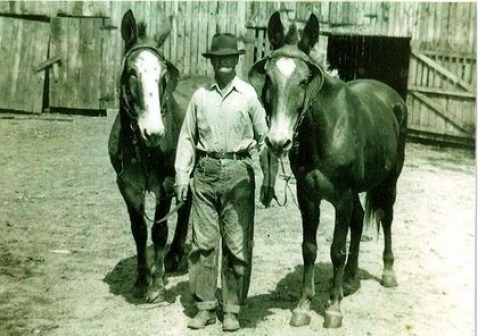

This is Mr. Blevins’s rendition of the farmhouse the family moved to when C. E. was only six years old.The farm near Jasper, Tennessee in Marion County had rolling hills and fertile flood plain fields beside the Sequatchie River. The family of six boys and two girls spent many long days farming the 130 acres, sharing their produce with the owners of the farm. Although they would eventually purchase the farm, there were many difficulties involved with subsisting during the depression years. They never had the use of a tractor or an automobile during these years. Two mules, plows, and a wagon served them as tools and transportation (see photo below of C. E.’s father).

C. E. learned to love nature while growing up on this farm. His father was a specialist at growing crops, and his mother instilled an appreciation for nature’s beauty. “She taught us how to get up in the trees and look down into the bird’s nests. She told us never to touch the eggs. And I remember looking at those eggs and thinking, 'These are the most beautiful things I have ever seen.' I’ve been fascinated with them ever since.On the farm, we watched all the birds, and learned all we could about them. We had to study the crows, too, because they could do some serious damage to our crops if we left them untended.We watched the barn swallows make their nests and kept the chicken hawks from eating our fowl.”

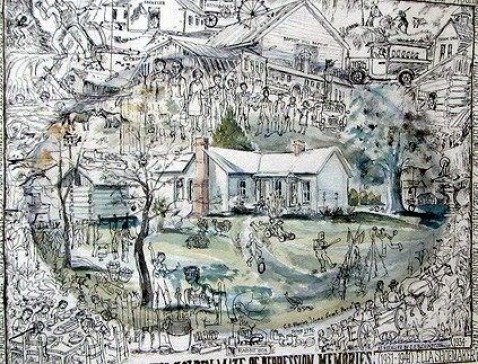

Even though the family now lived seventy miles south of Robbins, there were still trips back to their home place. Ella’s family, the Shoemakers, were storekeepers.C. E. would visit them and work in their store up until his high school years.There he would see his kinfolk’s houses, and the memories of these Appalachian homes are still vivid in his mind.See the painting below of “Uncle House" (pronounced "Huse") and Jonathan Blevins.

Even though the family now lived seventy miles south of Robbins, there were still trips back to their home place. Ella’s family, the Shoemakers, were storekeepers.C. E. would visit them and work in their store up until his high school years.There he would see his kinfolk’s houses, and the memories of these Appalachian homes are still vivid in his mind.See the painting below of “Uncle House" (pronounced "Huse") and Jonathan Blevins.

All of his paintings are done from memory. He doesn’t use photography to help with the details. Many Blevins homesteads were in the area, and some are now a part of the Big South Fork National Park.C. E. has cousins by the scores spread around the Scott County area. The Blevins family reunion is held every year at Pickett State Park, only miles from Robbins. Many of the kinfolk had to travel north to work in the automobile manufacturing plants.Some of them visit the family reunion in Scott County, bringing with them an incongruous mix of northern dialect, Irish genes, and Appalachian ingenuity.

After high school, C. E. joined the U. S. Navy and served on the U.S. Waldron battleship as a radioman during the Second World War. While on the ship, he served as the informal Chaplain on board, as there was no formal Chaplain.He led many worship services and received many thanks from the sailors on the Waldron.

C. E. and his bride, Laura Johnson Blevins, from nearby Haletown, both graduated from Peabody Teacher’s College, now part of Vanderbilt University, after the war.They raised five children while traveling and doing church ministry throughout Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee, mostly at Southern Baptist Churches.During these years, C. E. had acquired a Masters in English Literature and a Masters in Religious Studies from the Baptist Seminary in New Orleans.Ultimately, he and Laura made their home in Chattanooga, and now reside in Apison, Tennessee—a community not far from Chattanooga and Cohutta, Georgia.

Since retiring from missionary work, (Zambia, Africa 1981-1985) and teaching (public schools, Art Resource, Chattanooga), Mr. Blevins has spent fifteen years perfecting his passion for making the perfect egg.His passion is so intense he has probably made approximately 3o,ooo wild bird egg replicas, many clay bird figures, carvings and paintings.His replicas were sold for a few years through the Acorn Naturalist Catalogue and the Skulls Unlimited Catalogue.

His project now is to replicate the egg of each species that exists in the world, of which there are over 10,000.Although there are thousands that have not been documented, most of these are in South America, Africa, Russia and Asia.If he can get the information on exact length and width and coloration, he can make any exact replica.“Making all the eggs would be a lifetime project. I’m not sure I’ll have enough time, but I would like to."

“My main goal is just for people to see how beautiful the real eggs are, so people will appreciate the birds and learn to protect them. You know, without birds, it just might not be possible for humans to live. I’m not doing this for the money. I just thought this would be a good way to preserve nature’s beauty without bothering the birds.After the real eggs hatch, the mother bird sometimes eats the egg, or they’ll take them away from the nest so predators won’t smell them and eat her babies.These eggs are something you don’t easily see, anyway, they’re so protectively colored.But that’s why I’ve spent all this time learning how to make them.The egg shape is not an easy thing to duplicate. In its own way it’s perfect, and beautiful, and I want everybody that wants to see them to be able to come to the museum and see what I’ve been marveling at all my life.”

After high school, C. E. joined the U. S. Navy and served on the U.S. Waldron battleship as a radioman during the Second World War. While on the ship, he served as the informal Chaplain on board, as there was no formal Chaplain.He led many worship services and received many thanks from the sailors on the Waldron.

C. E. and his bride, Laura Johnson Blevins, from nearby Haletown, both graduated from Peabody Teacher’s College, now part of Vanderbilt University, after the war.They raised five children while traveling and doing church ministry throughout Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee, mostly at Southern Baptist Churches.During these years, C. E. had acquired a Masters in English Literature and a Masters in Religious Studies from the Baptist Seminary in New Orleans.Ultimately, he and Laura made their home in Chattanooga, and now reside in Apison, Tennessee—a community not far from Chattanooga and Cohutta, Georgia.

Since retiring from missionary work, (Zambia, Africa 1981-1985) and teaching (public schools, Art Resource, Chattanooga), Mr. Blevins has spent fifteen years perfecting his passion for making the perfect egg.His passion is so intense he has probably made approximately 3o,ooo wild bird egg replicas, many clay bird figures, carvings and paintings.His replicas were sold for a few years through the Acorn Naturalist Catalogue and the Skulls Unlimited Catalogue.

His project now is to replicate the egg of each species that exists in the world, of which there are over 10,000.Although there are thousands that have not been documented, most of these are in South America, Africa, Russia and Asia.If he can get the information on exact length and width and coloration, he can make any exact replica.“Making all the eggs would be a lifetime project. I’m not sure I’ll have enough time, but I would like to."

“My main goal is just for people to see how beautiful the real eggs are, so people will appreciate the birds and learn to protect them. You know, without birds, it just might not be possible for humans to live. I’m not doing this for the money. I just thought this would be a good way to preserve nature’s beauty without bothering the birds.After the real eggs hatch, the mother bird sometimes eats the egg, or they’ll take them away from the nest so predators won’t smell them and eat her babies.These eggs are something you don’t easily see, anyway, they’re so protectively colored.But that’s why I’ve spent all this time learning how to make them.The egg shape is not an easy thing to duplicate. In its own way it’s perfect, and beautiful, and I want everybody that wants to see them to be able to come to the museum and see what I’ve been marveling at all my life.”